|

|

|

|

| Home • Biography • Reviews • Calendar • Press • Recordings • Tickets | ||

|

|

Program Notes

2010/2011 Season

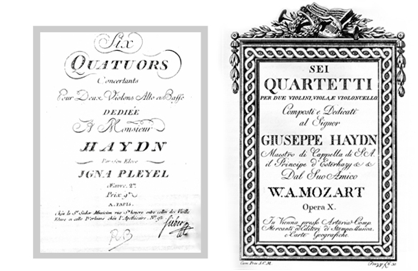

Dedicated to Haydn II September 2010 Such was Haydn’s fame and influence as a composer for string quartet that at least 16 sets of quartets were dedicated to him during his lifetime. Perhaps the most famous were the six written by his younger friend Mozart. The first edition of Mozart’s “Haydn Quartets” carries a flowery but nonetheless heartfelt letter by Mozart written in Italian and dated Vienna, September 1st, 1785: To my dear friend Haydn.

Students of Haydn I November 2010 Haydn had many pupils during his long life, both those he taught directly and those whose study of his works would qualify them as pupils even if they had never met Haydn. Among those who had personal instruction from him are two of the composers featured on the New Esterházy Quartet’s Thanksgiving weekend programs in San Francisco and Palo Alto. One became famous, one fell into obscurity. One was listed among Haydn’s “best and most grateful students” and one was reported to have said that he “never learned anything” from Haydn. Franciszek Lessel was a teenager when he left Poland for Vienna to study with Haydn. He remained there for a decade, returning to Warsaw in 1810 only after Haydn’s death. Among his compositions were 8 or 11 string quartets, depending on which source you trust. It seems, however, that the Quartet in Bb the New Esterházy Quartet performs is the only one that survives complete, the others lost either to the vicissitudes of Polish history or to the neglect of collectors. We were fortunate to secure parts copied by a Polish quartet from a manuscript score owned by the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris which has been subsequently lost, misplaced, misfiled or otherwise gone missing from the shelves. Initially sent from Bonn in late 1792 to (in the words of Count Ferdinand Ernst von Waldstein) “receive Mozart’s Spirit from Haydn’s Hands” Beethoven studied strict counterpoint with Haydn until Haydn’s departure for England in early 1794. The stories of the various fallings-out and misunderstandings between Haydn and Beethoven can be seen in the context of both Beethoven’s own difficult personality as well as a generational conflict between the two. In spite of financial independence in his last years, Haydn loyally served the aristocracy throughout his entire life, whereas Beethoven was notoriously unwilling to subordinate his worldly and spiritual independence to the demands of employers and patrons. While Haydn wore the peruke wig of the 18th century for reasons of hygiene as well as fashion, Beethoven wore his hair au naturel, even disheveled, in a style that continues to characterize rebellious spirits to this day. It is difficult to hear the direct influence of Haydn on either composer. There is an echo at the end of the exposition of Lessel’s first movement of the end of the first movement of Haydn’s Op. 77, No. 2, written about the same time as Lessel began his studies with Haydn. Lessel’s quartet was written, however, a quarter-century later. Although he did have a course of study with Haydn (“for those who could afford to pay, 100 ducats for the course, one half payable in advance, the other at the end” according to Haydn’s biographer Albert Christoph Dies), Beethoven seems to have profited more from the study of Haydn’s works than from the personal attention of the elder composer to his counterpoint exercises. Beethoven’s choice of genres, including piano sonatas, piano trios, string quartets, and symphonies, as well as his formal procedures and irregularities of accent and harmonic language show a deep indebtedness to Haydn.

Students of Haydn II February 2011 When we think of Beethoven, what image comes to mind? Rude and slovenly with hearing and drinking problems, or a sublime genius, or both? Like Walt Whitman Beethoven and his self-contradictions contain multitudes. And like Whitman, for better and for worse, he set the path for succeeding generations of creators who would imitate what they could of his achievements. A successful imitation of Haydn is a very difficult item to produce, since Haydn's eccentricities are visible against a backdrop of well-known designs and proportions, whereas Beethoven's inspirations often distort the background of common usage so much that it is difficult to know what it is he is referring to or making fun of. The follower is then left with nothing to build from but his own whims, which are likely to be far less inspired than Beethoven's. That is, it is easier to write a crazy scherzo than a truly original minuet. The next program in the New Esterházy Quartet's series featuring Haydn & His Students has an early quartet by one of his favorite and most successful students and also the last quartet of his most difficult and infamous student. Ignaz Pleyel's Op. 1, No. 3 is a genial and sonorous two-movement piece, the first in the 6/8 "hunting" time, the second variations. Beethoven's Op. 135 on the other hand, contains within its brief span multitudes from the vulgar to the exalted. The first movement is in the best "conversational" style pioneered by Haydn, the subjects seemingly morphing and recombining constantly, as if those conversing were trying to engage in an early 19th century form of multi-channelling. The Scherzo has left the minuet so far behind that one seems transported to some sort of cargo cult ritual that parodies without fully understanding what had been briefly glimpsed of a foreign visitor's ways. A feature to listen for is the possessed and over-the-top dance of the first violin above a figure in the lower strings that is repeated four dozen times beginning as loud as possible and ending as quiet as possible. After this business, the slow movement offers one of the most beautiful and heart-felt tunes ever written. And then, that most difficult to reach conclusion: Does it have to be? Yes, it must be! This mysterious Q&A is the portentous introduction to a seemingly simple-minded movement. Coming as it does at the end of Beethoven's life, the musical setting of the question "Muß es sein?" has been taken to carry all manner of metaphysical meaning, but its origins are in a canon Beethoven wrote for Ignaz Dembscher (pictured), an arrogant official of the Austrian court. After he skipped the premiere of Beethoven's Op. 130 quartet, he claimed that he could hire a better performance at home. So when he asked Beethoven for the parts, Beethoven let him know that he'd have to pay the price of admission to the concert he didn't attend. Dembscher, astonished at Beethoven's presumption, asked if that really must be, and a four-voice canon was Beethoven's answer, asserting that yes, it really had to be so. The musical substance of this musical rebuke then became the last movement of Beethoven's last quartet, an out-of-control in-joke. To provide the linchpin to this concert, the New Esterházy Quartet play also Haydn's beloved Op. 50, No. 5, The Dream.

Dedicated to Haydn IV May 2011 From Stockholm Haydn received a set of three quartets with which he was well pleased. The widow of their composer hoped that Haydn would aid their distribution and sale in Vienna, but Haydn, busy with his own late-blooming career in 1801, demurred, and so the name of Johan Wikmanson has remained in obscurity, like those of nearly all who dedicated quartets to the master. Yet, of those quartets we have played, Wikmanson's are the closest to Haydn in style and wit. The second movement of Wikmanson's first quartet is affectively another of The Seven Last Words, the work that Haydn considered his finest, and one we will play next season. What are the rewards to be found in quartets by composers from Sweden, Poland, France, and Germany dedicated to Haydn? They give us an idea of the greater landscape from which the peaks arise, they give us a wider and deeper view. Concertgoers tend to visit the peaks alone, as if the great classics were exotic islands rising above an undifferentiated ocean. Below the surface of the acknowledged masterpieces, however, is an unfamiliar and unexplored terrain, a musical ecosystem of interdependent lives and compositions that the New Esterházy Quartet enjoy sharing with our listeners. This concert also features another quartet by a composer who without a doubt stands tall above the waves of history. Mozart dedicated a set of six quartets to his beloved friend, and each of the "Dedicated to Haydn" concerts has presented one of these masterworks. The Quartet in Bb is known as The Hunt, because its first movement opens with a jaunty, cantering theme that is reminiscent of a horn call from horseback. Also on the program is Haydn's Op. 33 no. 6. This quartet may have inspired Mozart’s, as its opening movement is in the same spirit and meter.

2009/2010 Season

Haydn's quintet is one of his earliest surviving works, perhaps written for an outdoor serenade during the time when Haydn as a teenager was eking out a living after he lost his job in the Vienna Boys' Choir due to advanced adolescence adversely affecting his soprano voice. Mozart's is the earliest of his six quintets, written in Salzburg at the end of 1773 when he, too, was still a teenager. Our November concert was a sampler from Haydn’s half-century of quartet writing. Now for the final concert of our historic Haydn Cycle, the New Esterházy Quartet offer you a rich plate of the ripest fruits of Haydn’s maturity. These four masterworks date from the last decade of Haydn’s activity, when he was at the height of his powers, the toast of London for his late symphonies and acclaimed in Vienna for his oratorios The Creation and The Seasons. During the same period he wrote over 20 string quartets, the last outpourings of a man we have come to admire for his discipline, his wit, his knack for civilized discourse, and his rare balance of pride and humility. We hope to share with you these gifts that he packaged for our delectation over 200 years ago.

Haydn’s Predecessor at Esterházy Grave–AllegroGregor Joseph Werner (1693–1766) Gregor Joseph Werner entered the employ of Prince Paul Anton Esterházy in 1728, when Werner was 35 and the Prince half his age. Haydn was hired by Paul Anton to be Werner’s assistant 33 years later in 1761. The next year the Prince died and was succeeded by his brother Nicholas who became Haydn’s longest-lived and most important patron from the Esterházy family. Werner himself died somewhat infirm four years later, his life’s work of sacred music in the older polyphonic style outdated and ignored, while Haydn’s more up-to-date music found increasing favor with the new Prince. Over four decades after Werner’s death, which resulted in Haydn’s promotion to Kapellmeister, Haydn arranged for the publication of a set of six introductions from Werner’s sacred oratorios “out of particular esteem for this famous Master…” (as the you can see in the excerpt from the title page printed in your program). Today we play the fourth of these, originally to Werner’s The Prodigal Son of 1747, consisting, like all of them, of a slow prelude and a quick fugue. This strict contrapuntal quartet style had been much favored by Emperor Franz Joseph II in Vienna until his death in 1790. Perhaps Haydn’s publication represents not just a backward glance on his predecessor at Esterházy but also to the politically liberal but musically conservative Hapsburg emperor. Haydn’s Brother AndantinoJohann Michael Haydn (1737–1806) Mikey, Joes’s little brother, was born 5 years later. They sang together in the boyschoir St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, and after their voices broke pursued different career paths in music. While Joseph slowly became the most celebrated composer in Europe, Michael ended up in Salzburg as a colleague of Leopold Mozart. Michael Haydn’s students included Carl Maria von Weber and a musician who later became one of Joseph’s favorite students, Sigismund Neukomm. We shall hear more about Neukomm later in the afternoon. As a composer Michael was best known for his sacred music, but he did write string quartets and also quintets with an additional viola, a format that became a favorite of his younger colleague, Leopold’s son Wolfgang. When Mozart was fired, literally kicked out of his position in Salzburg 1782, it was Michael who succeeded him as court and cathedral organist. The letters of the Mozart family are filled with references and gossip about Michael Haydn, sometimes praising his music, sometimes filled with professional jealousy, and more than once commenting snidely on his occasional drunkenness. Among his dozen or so quartets is the single movement rondo we play for you today. Haydn’s Patriotism Variations on Gott! erhalte Franz den Kaiser Inspired by God Save the King and commissioned by the Hapsburg rulers of Austria, Haydn at the end of 1797 wrote the only national anthem written by a major composer. The backstory is extensive and convoluted. The end result is that Haydn’s Austrian national anthem, with an entirely different set of words is now the national anthem of Germany, and Austria is left with a selection from Mozart’s Freemason Cantata, with words fitted to it in 1947, words which have been recently attacked by the Minister for Women because they include such usages as “sons”, “fraternal”, and “Fatherland”. The original idea was to promote patriotism and acquiescence to the so-called reforms of Franz Joseph II in the runup to the Napoleonic Wars. Whether the reforming Kaiser was an oppressor or a liberal is a debate that is no more settled today than whether our own liberals or conservatives are the true friends of liberty and justice. The song which repeatedly calls for the preservation of Emperor Franz was first performed on February 12, 1797, his 29th birthday, in theatres and opera houses throughout the Austrian territories. Not long afterwards Haydn included the by-now well-known melody as the theme for a set of variations in the third quartet of his Op. 76. The success of the tune, and its combination of piety and patriotism served Haydn well in his last years. After he had given up composition and all public appearances, he still made it a habit to play this piece at the piano every day, even during Napoleon’s bombardment of Vienna in May of 1809. His friend and copyist Elssler reported that he played it on May 26 “with such expression and taste that our good Papa was astonished about it himself . . . and was very pleased.” Afterwards he was assisted to bed, and died 5 days later. Haydn’s Pupils I Menuetto: Allegro from Op. 2, No. 2Anton Wranitsky (1761–1820) In the last years of his life Haydn was frequently interviewed by the journalist and diplomat Georg August Griesinger. In the course of one of these visits Haydn referred to a dictum by a theorist concerning the rules of composition. “What does that mean?” asked Haydn. “Art is free, and will be limited by no pedestrian rules. The ear, assuming that it is trained, must decide, and I consider myself as competent as any to legislate here. Such affectations are worthless. I would rather someone tried to compose a really new minuet.” That Haydn would combine a declaration of artistic independence with an interest in the, by then, old-fashioned minuet should not surprise us. Haydn was a minuet kind of guy. There are 78 minuets in his 68 quartets, and a 104 in his symphonies, plus all those that are in his divertimenti, trios, sonatas, duets, and including the sets of dances he wrote for fashionable Viennese balls, there could easily be a thousand Haydn minuets! Those he wrote for dancing show all the signs of his art, and those he wrote as commentary on minuets, meta-minuets, as variations on the rhythmic and metrical structures of the dance, show him at his most fanciful, his most imaginative. No wonder, then, that even at the end of his life he was interested in what others might do with a minuet. With that in mind, we have assembled a couple of suites of minuets by his students. Moravian violinists Anton Wranitsky and his brother Paul took part in early performances of Haydn’s Creation under the composer’s supervision. Ignatz Pleyel was one of Haydn’s favorite students, who later was brought to London to compete with his teacher when Haydn was there leading concerts of his own music. They attended each other’s concerts and enjoyed meals together afterwards. Pleyel was the first of over a dozen composers to dedicate a set of string quartets to Haydn, his op. 2 of 1784. We will play a quartet from that set in our April concert. Interestingly enough, there are no minuets in Pleyel’s Op. 2 except for the brief, transitional dance which we play today. Was Pleyel too intimidated by his teacher to include minuets in these quartets? Franciszek Lessel was Polish, and the political misfortunes of his country have resulted in nearly all of his music, including nine quartets, being lost. The single source for his Quartet, Op. 3, however, has only recently disappeared from the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris. We were able to find parts in Warsaw that were hand copied from the Parisian source before the French lost it. Haydn’s English friend William Shield, who attended concerts in London and traveled with him on touristic jaunts, declared that he had learned more from hanging out with Haydn during a four day excursion than he had done by study in any four years of his life. After intermission you’ll hear a minuet by Peter Hänsel, whom Haydn recommended in a letter to Pleyel as “one of my pupils in composition…a charming young man of the best character, and also a good violin player.” A quartet from Hänsel’s Op. 2, will be heard in one of our Dedicated to Haydn concerts next season. Johann Nepomuk Hummel studied with both Haydn and Mozart, and went on to become a serious rival to Beethoven as a performer on the piano. He published only three quartets, from which we have lifted a minuet whose trio features some Alpine yodeling. From the last pupil of Haydn in our second and last suite we play the last minuet so-named from his 15 string quartets. It is a nostalgic, backward glance at a dance that served Haydn all his creative life. Haydn’s Pupils II Menuetto: Moderato from Op. 27, No. 1Peter Hänsel (1770-1831) Haydn's Farewell Der GreisJoseph Haydn Gone is all my strength, old and weak am I, Andante, to the Unforgettable Chief Conductor In 1796 Haydn wrote 13 songs for vocal quartet to various German texts. The first four bars of Number 5, The Old Man, served as Haydn’s greeting card ten years later, when he had given up attempting to compose, due to advanced age and exhaustion. In your program you can see opening of Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim’s text in Haydn’s hand, as well as the apologetic greeting card of 1806. Following our instrumental version of the partsong Der Greis, we will play a short Andante by Maximilian Stadler, a friend of Haydn’s from the beginning of his career. Stadler’s treatment of the open of the song, the theme of which appears on the greeting card, is from a manuscript copy made available to us by the Hungarian National Library. We doubt that it has been heard before in the Bay Area. If I say anything more about these two brief pieces there is a risk of the talk lasting longer than the music! Haydn's OratoriosJoseph Haydn Haydn’s late career, after the death of Prince Nicholas Esterházy in 1790, was a series of public and artistic triumphs. When Johann Peter Salomon, a German violinist and concert promoter heard of the Prince’s death, he rushed immediately to Vienna, knocked on Haydn’s door, and announced “I am Salomon of London, and I have come to fetch you.” Haydn arrived in London on New Year’s Day of 1791 and became a sensation. He also made sensational amounts of money. Already familiar on paper and through chamber performances with Handel’s music, in England he heard for the first time the full effect of Handel’s oratorios, particularly the choruses. For instance, in June of 1791, he heard an orchestra and singers numbering over 1000 perform at a Handel Festival in Westminster Abbey. These experiences led to the composition of The Creation and The Seasons. The oratorio version of the 7 Last Words of Our Savior from the Cross, which originally was an orchestral piece, was occasioned by an inferior setting by a provincial German musician, which Haydn felt that he should reply to with his own version. We are fortunate to have arrangements for string quartet of all three of these major oratorios. The 7 Words arranged by Haydn himself was published at the same time as the orchestral version and an arrangement for piano solo. The Creation in an anonymous arrangement was published about 5 years after the premier in 1798. The arrangement of The Seasons appeared shortly after the oratorio. It was done by Sigismund Neukomm, listed along with Pleyel and Lessel by an Griesinger as his best and most grateful pupil. Michael Haydn wrote appreciatively to Neukomm that the arrangement “will bring you the greatest honor also in the far, far future, because you have been able to put such a fully orchestrated work as The Seasons into four single voices without the finest connoisseur being able to miss anything.” The New Esterházy Quartet intend to present all three oratorios in future seasons. The three excerpts we play today as a suite are instrumental pieces in the originals. The first is a depiction of the primordial universe before the Big Bang, when God said “Let there be Light. And there was Light.” Before that, all is darkness on the face of the deep. The second depicts the stormy transition from winter to spring, which in the poem by James Thomson that inspired the German libretto, reads: The third is the earthquake that follows upon the death of Christ, which in the Matthew is described as: Haydn's Most Beloved Piece Not By Haydn Andante cantabile from "Op. 3, No. 5"Roman Hoffstetter (1742-1815) The Bavarian composer Roman Hoffstetter wrote in 1802 that “everything that flows from Haydn’s pen seems to me so beautiful and remains so deeply imprinted on my memory that I cannot prevent myself now and again from imitating something as well as I can.” It seems that he did this so well that six of his quartets were published in Paris in 1777 as Haydn’s. When Pleyel produced his pioneering complete edition of Haydn’s Quartets in 1801 he included the Hofstetter set as Op. 3. It is from Pleyel’s edition that we have our tradition catalogue of Haydn Quartets by opus number, but recent scholarship has agreed that Haydn’s Op. 3, with its beloved Serenade, is no longer by Haydn, and so it gradually will sink into obscurity along with the thousands of quartets by composers as unknown as Hofstetter. But this afternoon we offer it as our last encore to the complete Haydn Quartets.

In a letter to his daughter Nannerl, dated Salzburg, January 22, 1785, Leopold Mozart reported that “...last Saturday [Wolfgang] performed his six quartets for his dear friend Haydn and other good friends, and that he has sold them to Artaria for a hundred ducats.” The New Esterházy Quartet rehearses and performs Mozart's Quartets from facsimiles of this elegant and informative Artaria first edition. It carries an elaborate dedication to Haydn, written without expectation of aristocratic reward, an acknowledgment of Haydn's prestige. Ignaz Pleyel was one of Haydn’s “best and most grateful pupils" according to Haydn’s friend and biographer Georg August Griesinger. Pleyel’s second set of string quartets was dedicated to his teacher in 1784, the first of more than a dozen sets of quartets dedicated to Haydn during his lifetime. Pupil and teacher found themselves set up as rivals before the British press and public a decade later. Haydn’s presence made the concerts promoted by Johann Peter Salomon in London during the early 1790’s a tremendous success, and so a rival concert series, failing to lure Haydn away with an offer of more money, engaged Pleyel to counter Haydn’s popularity with the public. The two “rivals” greeted each other affectionately, attended each other’s concerts, and dined together afterwards. Haydn’s string quartets Opp. 71 & 74 were written specifically for Salomon’s quartet to play on his London concert series. The loud opening chord and the silence afterwards were to get the attention of the audience, no longer guests in a private house, but chatting and doing business in a public concert room. With these quartets, chamber music which was formerly enjoyed primarily by the players themselves in private becomes concert music for a paying public.

2008/2009 Season

Haydn at the Opera October 2008 Dear Lover of Fine Singing, For the first concert of our second season, the New Esterházy Quartet invites you to some of Haydn’s most operatic quartet music. As today the dream of every young slugger is The Show (major league baseball), of every big-voiced hoofer is Broadway, of every YouTube poster is Hollywood, so the ambition of every composer since the beginning of the seventeenth century has been the Operatic Stage. Haydn got more than he bargained for when he signed with the Esterházy family—beginning in the late 1770’s there was either a play or an opera produced every evening the Prince was in residence. Even the indefatigable Haydn could not fill all that demand, so new operas and new productions of old operas from over two dozen other composers in addition to Haydn’s own were heard in the seasons from 1776 to 1790. By way of example, there were 89 operatic performances in 1785 , 125 in 1786, and 98 in 1787. For each of these Haydn had responsibility to prepare the parts, coach the singers, rehearse the orchestra, and lead the performances, in addition to composing new arias and ensembles for other composers’ works when they needed refurbishing. Haydn knew his opera. And so did his listeners and players. So it’s not surprising to hear strong operatic elements in his quartets. In this Saturday’s concert we’ll play everything from Overtures to Finales, with Arias and Mad Scenes between. Haydn in the Morning I November 2008 On Saturday afternoon the New Esterházy Quartet continues its Haydn Cycle with the first of four concerts wishing its listeners a Good Morning. The featured quartet is Op. 50, No. 5, known as “The Dream” for its remarkable slow movement, floating serenely away after a witty first movement and before an earthy minuet. The first half of the program contains the first two quartets of Haydn’s Op. 9, the first time we have played from this collection. His earliest quartets, one of which we also present on Saturday, have five movements, but with Op. 9 Haydn gave us the four movement format that became standard for the classical string quartet, at least until Beethoven began the experiments of his late period. Quirky and innovative, these Op. 9 quartets are little known, and we look forward to sharing all of them with you.

Haydn in the Morning IV (Featuring "The Razor") March, 2009 The story goes that the London publisher John Bland visited Haydn at Esterházy in 1789, and Haydn, while having difficulty shaving, exclaimed in exasperation that he would give his best quartet for an English razor. Bland, it is said, exchanged his own for Haydn’s Quartet in F minor, which became known as Op. 55, No. 2 “The Razor.” There are all sorts of sound reasons why this story could not true, or at least why the F minor quartet is not the one that Bland got for his blade. Nevertheless, we have been stuck with the story for over a century and a half, so we honor it in making “The Razor” the apotheosis of our series Haydn in the Morning. And there are good reasons for supposing that Haydn might have thought this his “best quartet.” Joining it in our program are three earlier quartets, including the first of the set of six that Haydn dedicated to Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia, in return for a golden ring that the King had sent him. Our Haydn was evidently a collector of precious metals!

2007/2008 Season

Last Saturday Albert Fuller, an influential harpsichordist, conductor, and author, as well as teacher, mentor, and guide to several generations of performers, passed away at his home in Manhattan. He was a Professor at the Julliard School, as well as founder of the Aston Magna Foundation for Music and the Humanities and the Helicon Foundation. “The authenticity I'm interested in,” Mr. Fuller told the New York Times in 1989, "is our contemporary sense of the reality of the past, and what the music we have inherited has to do with us today. I believe that music is a window into the unconscious, and the miracle of it is that it lets us get close to what Beethoven, Bach and Mozart were thinking." Mr. Fuller listened to a recording of our New Esterhazy Quartet's first concert a couple of months ago. He wrote then and said: "We loved the program and listened to every note of it with immense pleasure.....God bless you all! May you finish the series as you have so well planned....." With that reassuring and appreciative message he sent a contribution as an additional measure of his support of our important mission to perform the string quartets of Haydn at the very highest level. Our concert today is dedicated to the memory of the New Esterhazy Quartet’s dear friend and mentor, Albert Fuller. Haydn’s Fugues doesn’t refer to any psychological difficulties in this most sane of all great creative geniuses. Rather, in the four quartets we present in December you will hear Haydn writing in or with reference to the stilo antico, the contrapuntal style called fugue in which the four musical voices all share the same melodic material, layered and overlapped in the most ingenious combinations. This was the musical texture in favor with the Habsburg Court, conservative and with overtones of the style of religious music since the Renaissance. Haydn, ever playful, finds in these and other quartets ways to use the fugal style for extraordinary expressive and dramatic effects. Haydn in Bethlehem February 2008 We will be playing Haydn Quartets from the archives of the American Moravian settlements in and near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. And we will be playing not from the latest scholarly editions of Haydn, but from copies of the actual parts used by 18th century American musicians. The Moravian Church traces its origins back to the followers of Jan Hus (1369-1415), a Czech priest and reformer who was executed as a heretic in 1415. Hus's followers organized a society called the "Unity of the Brethren" (Unitas Fratrum) in 1457, devoted to piety and congregational participation in worship. For about 200 years this group led a precarious life, mainly in Bohemia, Moravia, and Poland. They made significant contributions in hymnody, theology, and education, but the Counter-Reformation and the Thirty Years' War nearly destroyed the small church, forcing its remnants underground. In 1722 some of the descendants of these "Bohemian Brethren" settled on the estate of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf in Saxony, and under his protection they re-established their church. The first permanent Moravian settlement in North America was established in Pennsylvania in 1741 and named Bethlehem. Other settlements were founded soon after, in Nazareth and Lititz, PA; and in Bethabara, Bethania and Salem in North Carolina. During the eighty years from about 1760 to 1840, American Moravians wrote hundreds of anthems, duets, solo sacred songs, and instrumental pieces, and collected hundreds of others—both printed and hand copied. Among the music collected and copied by the American Moravians were string quartets of Joseph Haydn. The New Esterházy Quartet will play three quartets from Moravian sources, using reproductions of the original 18th century parts. Two quartets are from 18th century editions published in Berlin and Amsterdam and one is in the hand of Abraham Levering of the Lititz (Pennsylvania) Moravian Collegium Musicum. The concert is called “Haydn in Salem” not because of any connection with witchcraft (that was in the Puritan colony!) but with the Moravian settlements in Carolina. Thanks to the Moravian Music Foundation, we have photocopies of Haydn Quartets that were played and enjoyed in 18th century America. The four quartets from the Salem (North Carolina) archive include pieces from Op. 2, Op. 17, Op. 20, and Op. 77. Playing from 18th century parts presents special challenges and rewards, and we hope that you will join us for this adventure in living history. The Moravian Church traces its origins back to the followers of Jan Hus (1369-1415), a Czech priest and reformer who was executed as a heretic in 1415. Hus's followers organized a society called the "Unity of the Brethren" (Unitas Fratrum) in 1457, devoted to piety and congregational participation in worship. For about 200 years this group led a precarious life, mainly in Bohemia, Moravia, and Poland. They made significant contributions in hymnody, theology, and education, but the Counter-Reformation and the Thirty Years' War nearly destroyed the small church, forcing its remnants underground. In 1722 some of the descendants of these "Bohemian Brethren" settled on the estate of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf in Saxony, and under his protection they re-established their church. The first permanent Moravian settlement in North America was established in Pennsylvania in 1741 and named Bethlehem. Other settlements were founded soon after, in Nazareth and Lititz, PA; and in Bethabara, Bethania and Salem in North Carolina. During the eighty years from about 1760 to 1840, American Moravians wrote hundreds of anthems, duets, solo sacred songs, and instrumental pieces, and collected hundreds of others—both printed and hand copied. Haydn in London – The Wisdom of Salomon April 2008 In early 1790 Haydn’s Prince Nicholas Esterházy died, leaving Haydn after 30 years of service free to set his own agenda. He moved immediately to Vienna and took lodging in the house of a friend. But in December of that same year a German violinist working as a concert producer in Britain appeared abruptly in Haydn’s rooms with a summons that would dramatically change Haydn’s life and works: “I am Salomon, I have come to take you to London.” Among the numerous compositions Haydn took to London to perform on Salomon’s concerts were the six Quartets, Op. 64, which he had just finished before he left. For his return trip in 1794, he composed six more, Op. 71 & 74. This Saturday, April 12, at 4pm in St. Mark’s Lutheran Church (San Francisco) the New Esterházy Quartet offer you three of these pieces that Haydn offered to his London audiences some 215 years ago. The widely-traveled, multi-lingual Mozart is said to have reminded Haydn on the eve of his departure from Vienna that he was inexperienced with travel and foreign languages. Haydn brushed this warning aside by saying “Oh, my language is understood all over the world.” A Toast to Johann Tost May 2008 The New Esterházy Quartet offers a Toast to Johann Tost. This slippery character was a minor player in the drama of Haydn’s professional life. He was at one time the leader of Haydn’s second violins at Esterházy, later the husband of Prince Nicholas’s housekeeper, a wine merchant, a sales agent for Haydn’s Quartets, Opp. 54, 55, and 64, and the subject of several curious letters written by Haydn in the late 1780’s to his publishers—

We will play three quartets of the 12 that Tost had peddled on Haydn’s behalf, Op. 54, No. 1 in G, Op. 55, No. 3 in Bb, and Op. 64, No. 1 in C.

(415) 520-0611 |

mail@newesterhazy.org

|

|

newesterhazy.org - © 2009 - design: dehorde.nl |

||